Either make the tree good and its fruit good: or make the tree evil, and its fruit evil. For by the fruit the tree is known.

Christ, from the Gospel of St Matthew, Chapter 12

I have been meaning to talk about the wickedness of the financial system which funds the replacement of our civilisation for some time.

Today I bring this novel effort to get on all the naughty lists with a review of a new book about usury1.

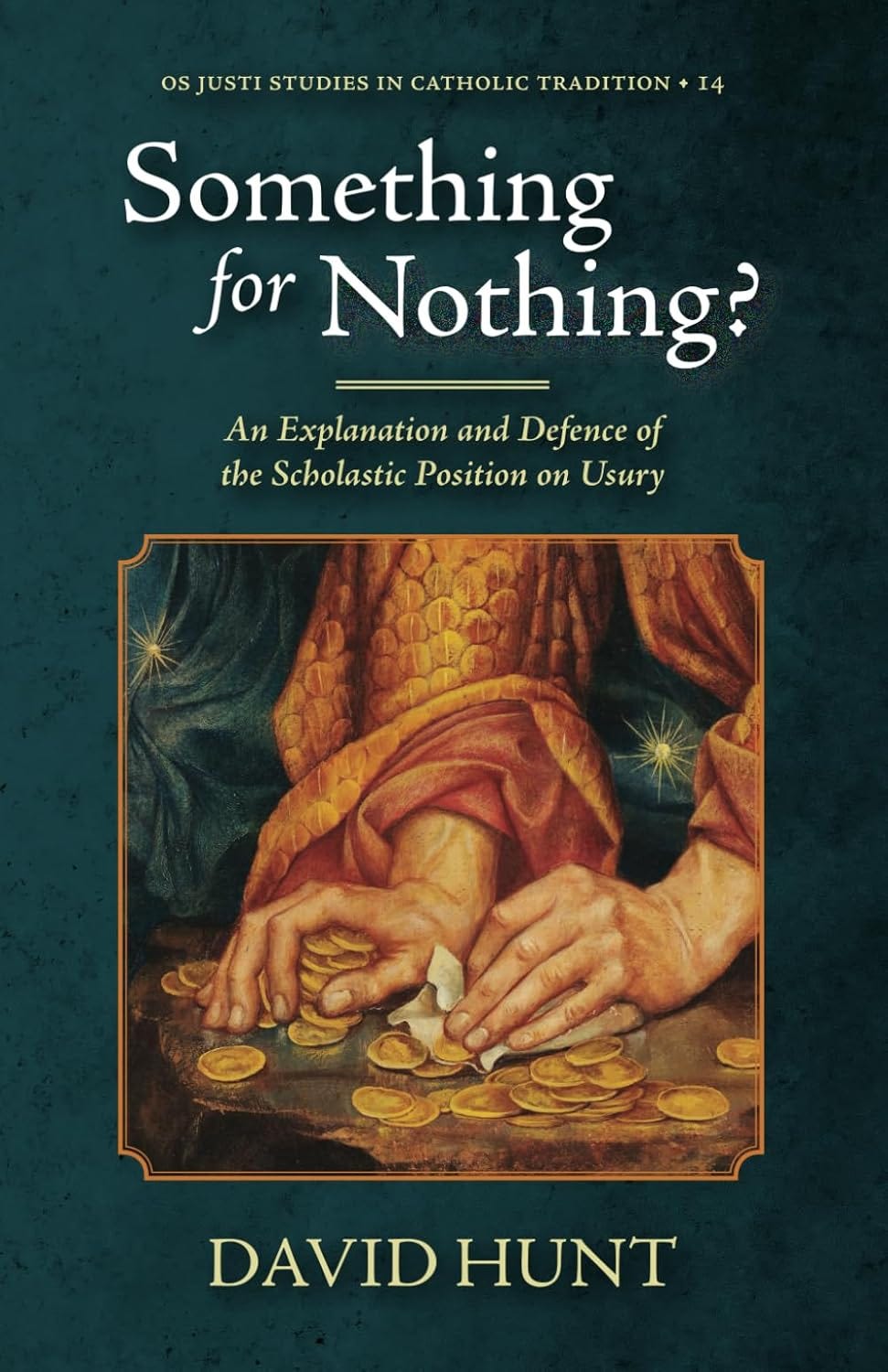

David Hunt’s Something for Nothing is the sort of book which is an education. It is brief, precise and has an explanatory power which reaches far beyond its subject.

We are told by the moneylenders that the temple belongs to them these days. Market worshippers from Ben Shapiro to the Austrian School will tell you that the mere mention of usury as a moral evil is a relic of the middle ages.

O generation of vipers, how can you speak good things, whereas you are evil? for out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaketh.

Matthew 12:34

That this is presented not only as an argument but as an answer should give you pause. The objections to usury, as Hunt shows clearly, cannot be gainsaid. This is the reason you are simply told the idea itself is old fashioned. We have this new vice now, you see. Look at how it glitters. We have no need of Christ’s advice these days.

A good man out of a good treasure bringeth forth good things: and an evil man out of an evil treasure bringeth forth evil things.

Matthew 12:35

With this fool’s gold is the Devil’s bargain sealed. Practically every evil of our times is presented as a shimmering novelty, with long-established wisdom dismissed as the habit of primitives.

This sleight-of-mind presents the wicked as the wise. That there is a deep rooted evil which has radically supplanted our civilisation is obvious. How it has done so is explained in this concise account of the monster of usury, created in the financial service of sin.

The question today is not whether we inhabit a civilizational crisis, but what can be done about it. David Hunt’s new book presents the case that traditional Catholic teaching can supply the answers.

“Radix malorum est cupiditas”, said St Jerome’s Vulgate in the first letter of St Paul to Timothy. The full quote, often translated as “the love of money is the root of all evil” is a theme renewed in this latest account of financial wickedness from Os Justi Press.

This book, like the memorable quote, delivers far more on examination than is offered at first glance. In Something For Nothing, the British traditional Catholic David Hunt gives the reader a whirlwind tour of Catholic teaching, Roman Law, Aristotelian logic and the pronouncement of past Popes to show precisely how the treasure of the Church lies not only in the salvation of souls, but in the power of its teaching to deliver us from evil today.

The evil here, of course, is usury – commonly understood to the charging of interest on loans. Hunt shows how and why this is not a total understanding of the sin of demanding “something for nothing”, with an analysis so complete and clear as to commend him as a future minister of finance for a Catholic state.

Yet his book has an explanatory power which reaches far beyond its subject. Though Hunt’s excellent formation in Aquinas lends his work the authority of an expert, its subject is rendered in a readable and digestible progression from the beginnings of the concept of usury to its present end.

If you read it, you will emerge from the experience with a better grasp of how the social reality you inhabit has been created, establishing obvious injustice and disorder as the basis of the new world order.

In a startling conclusion, he reveals that the condition of modern man under usury is that of a slave. Careful to show his working, his answers are all the more arresting as they also happen to be true.

Hunt begins by noting the significance of the difference between things. His point is initially about goods which are consumed by use (like wine and food) and those which are not (money).

This determines whether it is just or not to charge for them for having been used. It is said to be just to apply a charge for the use of money – a price – whilst the sum initially loaned is also returned in full. This is the something for nothing of the title – that the money made in interest is gained by no fair exchange, and with no loss to the lender.

Here Hunt’s subject provides an illustration of the disordered spirit of our age.

The noting of basic difference between things said to be the same is the basis of the undermining of our reality generally. Hunt’s book will arm the reader with the Catholic formation to combat this assault on the real, and on the natural order ordained by God. At a time of civilizational crisis, Hunt’s is a book which demonstrates that the Catholic Church has the answers.

It is the sort of book which teaches you how to think better about everything by examining one thing, and as such is a treasure in itself. Brief, at only 78 pages, it is sandwiched by a helpful glossary at the front, and informative appendices at the back, including the import of Roman law, the philosophy of Aristotle, the Summa of St Thomas, the Council of Vienne, and those of Popes Callistus III, Leo X, Pius V, Innocent XI, and Benedict XIV.

This sound basis in Catholic doctrine is partnered with a keen eye for the competing explanations of the counterfeit culture of the 20th century.

Hunt’s treatment of British economist JM Keynes provides on page 40 one of the most succinct summaries of the crisis of our times.

Keynes not only acknowledged but legitimized the wickedness of usury in a wider context of complete moral inversion, saying in 1963,

“For at least another hundred years we must pretend to ourselves and to every one that fair is foul and foul is fair; for foul is useful and fair is not.

Avarice and usury and precaution must be our gods for a little longer still.”

Keynes was quoting Macbeth here, a fable of cupidity in which ambition and lust for power corrupts the natural order completely. Murder and madness are the result. Keynes was speaking in defence of the construction of a new liberal order, backed by useful “avarice and usury”.

We are sixty years into his century, and the result has been the production of a similar and predictable tragedy in our entire way of life.

Hunt demonstrates that the Church teaches it is unjust to charge for non-existent things. This could also apply to the promises of Liberal Utopianism more generally. From the “barren metal” of Aristotle and the excellent arguments of Belloc, Hunt displays that the tradition of the church has ample treasure to restore our civilization from the ruin caused by these reckless dreamers, which he notes has fallen victim to a simple fascination with novelty.

Hunt shows the poverty of the modern notion that “old” means “redundant”, and new always “improved”, against the charge that tradition can be discarded because it was of its time.

He gives short shrift to the objection, made by libertarians and their Austrian economist heroes, that the rejection of usury was simply a mediaeval relic for which we moderns have no use. This is the same tactic used by philosophers more generally, as Hunt is aware, to get around the problem of Thomas Aquinas.

Robert F Kennedy says the US Federal Reserve2 “operates on behalf of a few Wall Street banks, and its function is to act like a pump. It is literally strip-mining the wealth and equity away from the American middle class.”

We have this new thing now, is the general idea. We have no need of this invincible wisdom we cannot counter. Hunt shows how this neophilia is simply a means of recasting old vices as refreshing innovations.

The vice here that is made virtuous is not only the love of money, but the lengths to which men will go to make these new virtues seem a necessity. Here, of course, the work becomes a critique of the counterfeit culture intended to replace that founded by the Catholic Church.

St Jerome’s original Latin, from the letter of St Paul to Timothy, gives a more complete understanding of the nature of this particular evil.

“Radix enim omnium malorum est cupiditas quam quidam appetentes erraverunt a fide et inseruerunt se doloribus multis”.

The root of all evil is cupidity, and men in pursuit of their appetite for greed have abandoned the faith, piercing themselves with many evils.

Cupidity is the desire “for goods of any kind” - except the Good, which is of course God. Hunt’s book is a manual for those would would be delivered from the evil which animates our times.

In a system which replaces everything with nothing through commodified desire, it is vital to understand the financial crime which powers it.

Usury has bankrolled and normalized the creation of this counterfeit culture, depriving not only your cash, but the rest of your life of genuine value. To read Hunt’s brief and illuminating book is to examine the root and not merely the fruit of the counter-civilizational experiment we inhabit.

My house shall be called the house of prayer; but you have made it a den of thieves

Christ, in the Gospel of St Matthew, Chapter 21

David Hunt’s Something for Nothing – An Explanation and Defence of the Scholastic Position on Usury was published by Os Justi Press on September 5th, and is available on their website and via Amazon.

If you would like to donate to my ongoing campaign to be humiliated at a brief show trial, thence to subsist on shoe-leather soup in some neo-Bolshevist nightmare box, please consider doing so here.

In this way you may make certain that I, the Midget of Misinformation, will get what I deserve.

First published on LifeSiteNews, last week.

For more on the nature of the Federal Reserve - and the central banking system in general, see here for an overview.

For a brief on the Federal Reserve as the “fulcrum of corruption”, see Richard C Cook’s excellent presentation here. Cook was a federal analyst for almost 40 years, with extensive experience of the US Treasury.

The City of London is another prime example of this. Only interested in the bottom line and not a proper support to the British economy and entrepreneurs.

Does Hunt's book cover the Bank of England?

Also you get into the Creature of Jekyll Isle yet?